Grade 12: The Suicide Battalion & Canada's Role In World War One

THE 46th Canadian Infantry Battalion (South Saskatchewan) was formed in Moose Jaw, SK, in February 1915. The battalion would end up playing a role in every major battle in which the Canadians took part from August 1916 until the Armistice.

With a 91.5% casualty rate (3,484 wounded and 1,433 killed, including Victoria Cross winner and Saskatchewan hero Hugh Cairns), the 46th became known as the Suicide Battalion.

World War 1 is commonly accepted as a turning point in history for both Canada and the world, yet we don’t often get the chance to hear about the experiences of the war from the men that were there in the trenches.

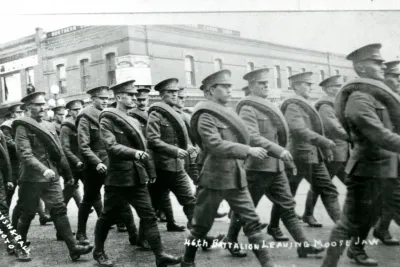

The 46th Battalion leaving Moose Jaw for the War, ca. 1915. PAS Photo R-A32277-1.

The 46th Canadian Infantry Battalion (South Saskatchewan)

“The Suicide Battalion” Oral History Project

The 46th Canadian Infantry Battalion (South Saskatchewan)

“The Suicide Battalion” Oral History Project

Between 1975 and 1977, James L. McWilliams and R. James Steel interviewed dozens of veterans from the 46th Battalion about their experiences during the war in order to include soldiers' first-hand accounts in their book,The Suicide Battalion (St. Catherines, Ontario: Vanwell Publishing, 1990). The audio recordings of these interviews were donated by McWilliams and Steel to the Provincial Archives of Saskatchewan as The 46th Canadian Infantry Battalion (South Saskatchewan) “The Suicide Battalion” Oral History Project.

Using excerpts from audio interviews with three 46th Battalion soldiers, what can we learn about Canada’s role in the Great War through the experiences of the Suicide Battalion soldiers?

Between 1975 and 1977, James L. McWilliams and R. James Steel interviewed dozens of veterans from the 46th Battalion about their experiences during the war in order to include soldiers' first-hand accounts in their book,The Suicide Battalion (St. Catherines, Ontario: Vanwell Publishing, 1990). The audio recordings of these interviews were donated by McWilliams and Steel to the Provincial Archives of Saskatchewan as The 46th Canadian Infantry Battalion (South Saskatchewan) “The Suicide Battalion” Oral History Project.

Using excerpts from audio interviews with three 46th Battalion soldiers, what can we learn about Canada’s role in the Great War through the experiences of the Suicide Battalion soldiers?

Jim Butterworth

Read Jim Butterworth's Attestation Papers from Library & Archives Canada

interviews with Jim Butterworth:

Trench Warfare – Jim Butterworth: Tape R-107 (5:50 minutes)

Raiding Parties – Jim Butterworth: Tape R-1075 (9:50 minutes)

Regina Trench & The Somme – Jim Butterworth: Tape R-1075 (9:09 minutes)

Ernie 'Jink' Jenner

Read Ernie 'Jinx' Jenner's Attestation Papers (Library & Archives Canada)

Interview With Ernie 'Jink' Jenner:

Passchendaele – Ernie ‘Jinx’ Jenner: Tape R-1059 (8:02 minutes)

E.D. (Eric Douglas) McDonald

Read E.D. McDonald's Attestation Papers (Library & Archives Canada)

Interview with E.D. McDonald:

Amiens – E.D. (Eric Douglas) McDonald: Tape R-1078 (9:48 minutes)

46th 'Suicide' Battalion Photos

Jim Butterworth(left) and Harold Brown (right) of the 46th Battalion. PAS Photo R-A14139.

Group photo of officers and N.C.O.'s of the 46th Battalion, taken at Wawre, Belgium, after Armistics Day, 1918. PAS Photo R-A14119.

Men of the 46th Battalion embarking at Regina, ca. 1915. PAS PHoto R-A14133.

46th Battalion leaving Moose Jaw for Camp Sewell (2nd Reinforcing Draft). PAS Photo R-A32277-2.

W. Hogg, J.B. Fraser, L.L. Smith, J. Fraser, and E.D. McDonald (marked with an X) with the 46th Battalion Canadian Infantry, posing in uniform at Bramshott Camp, England, 1917. PAS Photo R-A32265.

South Saskatchewan 46th (Overseas) Battalion in Reserves at Brewry at Lacollet, 1917. PAS Photo R-B14132.

Curriculum

Foundational:

- Know that the actions and policies of other nations influence the well-being of the Canadian people and nation.

- Know that the conduct of Canadian foreign policy has generated, and continues to generate debate within the Canadian community.

Knowledge:

- Know that by the end of the First World War, 600 000 Canadians had served in an army of four divisions. More than 60 000 Canadian military personnel were killed in the War.

Historical Thinking Concepts:

Evidence: How do we know what we know about the past?

Guidepost 1: History is an interpretation based on inferences made from primary sources.

Guidepost 2: Asking good questions about a source can turn it into evidence.

Guidepost 4: A source should be analyzed in relation to the context of its historical setting; the conditions and worldviews prevalent at the time.

Guidepost 5: Inferences made from a source can never stand alone. They should always be corroborated -- checked against other sources (primary or secondary).

Historical Significance: How do we decide what is important to learn about the past?

Guidepost 1: Events, people or developments have historical significance if they resulted in change. That is, they had deep consequences, for many people, over a long period of times.

Guidepost 2: Events, people, or developments have historical significance if they are revealing. That is, they shed light on enduring or emerging issues in history or contemporary life.

Guidepost 3: Historical significance is constructed. That is, events, people, and developments meet the criteria for historical significance when they are shown to occupy a meaningful place in a narrative.

Historical Perspective: How can we better understand the people of the past?

Guidepost 3: The perspectives of historical actors are best understood by considering their historical context.

Guidepost 4: Taking the perspective of historical actors means inferring how people felt and thought in the past. It does not mean identifying with those actors. Valid inferences are those based on evidence.

From The Big Six Historical Thinking Concepts by Peter Seixas and Tom Morton (Toronto: Nelson Education, 2013)