Charles Douglas "Dick" Richardson

- Born December 28, 1891, fifth of seven children born to Benjamin Parkin Richardson (a lawyer) and Margaret Ethel (née Austin) Richardson of Grenfell, Saskatchewan.

- After leaving public school, he worked as a school teacher for a year or two in the Moose Jaw area before becoming a student in the five year program at the Manitoba Agricultural College (M.A.C.) in Winnipeg.

- While at College, he was the president of his class, a keen debater, and editor of the college paper, The Gazette.

- In October 1915, he enlisted with the 4th University Company and went overseas in the spring of 1916 after graduating with a Bachelor of Science and Arts (B.S.A.).

- He served with the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry (P.P.C.L.I.) as a lance corporal in Belgium, where he was wounded at the Battle of Sanctuary Wood on June 2, 1916. He spent several months recovering in England before returning to service in France.

- He died on April 9 or 10, 1917, as a result of wounds sustained at the Battle of Vimy Ridge.

Context for the Charles Douglas (Dick) Richardson fonds

From Provincial Archives of Saskatchewan (PAS), R-E4571, Transcribed letters of Charles Douglas (Dick) Richardson, 1915-1917. These letters were donated to PAS in 1999. The excerpts from letters that are included in this package were written by Dick Richardson to Edna Chapman; and also by Pte Frank J. Whiting of P.P.C.L.I. to Mrs. B.P. Richardson, after her son Dick’s death in 1917.

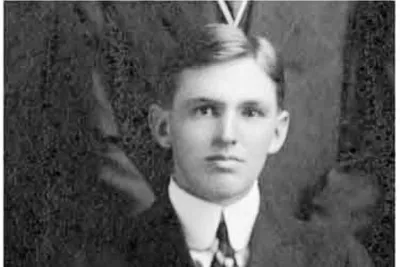

C. D. Richardson, MA Gazette Staff (Assist. Editor), 1914. Courtesy University of Manitoba Archives, Elizabeth Dafoe Library.

Letters from Dick Richardson

Letters from Dick Richardson

Letter #21, from Dick Richardson to Edna Chapman

P.P.C.L.1. [Canadian Expeditionary Force] C.E.F. France

April 28, 1916

Dear Edna:

France at last – just exactly 6 months to the day from the time I enlisted. I shall always remember Easter Sunday this year for that was the day we spent crossing from England. It took us about 6 hours to cross the channel.

At the present moment I am sitting beside our tent using a pile of blankets for a writing desk. I cannot tell you everything that is here, but being the Base, the troops are here for only a week or 10 days before proceeding to the firing lines. I expect we shall go about a week from today. Upon arriving this far Steve and I found that Jim Brown had been gone about 3 weeks, so we are anxious to catch up to him again.

I can say this much about France, as much of it as I have seen that it compares very favorably with England, so you know it is very beautiful. The leaves are just coming out and the fruit trees are in blossom. I hope I shall have a chance to visit a few orchards here when the fruit ripens.

Our training camp is situated in such a position that we have a 2 mile march uphill with full pack every morning and the return trip each evening. The weather is fearfully hot, like a day in July in Sask. or Man. Today we had a route march of about 7 miles, and the sweat of an honest 10 days work was plainly in evidence at the finish.

It is interesting to look down the lines of tents just now and notice what the fellows are doing. At every angle and position imaginable, some are writing, others smoking and talking in groups, others are cleaning rifles, some are singing, particularly around the canteen, and so many other things peculiar to a military camp that a civilian would find a visit quite a novelty. We do not notice it ourselves. It is now about 7 o'clock and still quite light. Steve is in the tent. I think he has the bed made ready for me. We have a good bunch in the tent with us, all of our company. In fact I have enjoyed the week here so far very much.

I am getting a pass, (Steve & I, I should say) to go to town tomorrow. No doubt we shall have an interesting time trying to talk French. Steve has the advantage of me there, in having lived in Quebec so many years that he has learned a good deal of French. However I am learning.

During our march from the point where we landed a distance of about 6 miles, the French children flocked around us like sheep, asking for pennies, biscuits, bully beef, and souvenirs. They knew that much English anyway.

That reminds me that bully beef & biscuits form a very large part of our rations nowadays. I wish I could send you a biscuit as a souvenir. They are made from whole wheat flour and I believe are very wholesome. Their chief properties, however, are their lack of taste, and their resistance to external forces, for of all the creations of modern bakers they are absolutely the hardest. However a biscuit goes a long way with a bottle of water and a can of bully! I do not mind the fare at all. There is lots of grumbling, but that quality is only a sign of a good soldier.

We have every Thursday off ordinary duty for the purpose of cleaning up the lines, washing our clothes and generally trying to recall the fact that we used to be civilized. Saturday afternoon is generally a holiday too and there is only church parade on Sunday so this may pretty properly be termed a 'rest camp'! Last but greatest of all, we don't have to (blance?) equipment and polish brass and buttons. The ceremonial frills and useless formality of Shorncliffe days are done. What we do now is learn those things we need to know and forget the rest.

I have not heard from you for over 2 weeks but I expect there is a letter or two somewhere in this little world, that does not seem quite so large as it used to, so I shall wait.

Excuse pencil -- circumstances you know -- and keep an occasional line and thought coming in this direction. They will both be returned, the latter with interest.

Till next time,

Sincerely,

Dick

Letter #25, from Dick Richardson to Edna Chapman

No. 13. General Hospital, Bologne, France

June 5, 1916

Dear Edna:

Perhaps you have heard something about the time we have been having. I hope I never have to go through it again. It was simply Hell! I cannot tell you much about it now but I shall later. Our regiment was almost obliterated. About 40 of us came back out of the two companies that held the front line. No. 1 Company on our right were all either killed or taken prisoner, not a single man came back. No.2 which is the company I was in were able to hold them off all day and all night until their artillery leveled all our trenches and left us with only 40 men, many of them wounded. They got through the trenches on our right and got behind us opening up machine guns from both sides so that we were forced to retire on our left over 400 yards of open country, with the whole of it a mass of flame from bursting shells and swept by machine guns. I had to crawl most of the way as a piece of shrapnel early in the day had put me out of commission opening up my right side to the depth of my ribs and about 5 inches long and 2 inches wide. That is why I am now holding down one of the comfortable beds here in Bologne having been brought down by train last night. Next time I write I shall be in England, I expect, for my ticket reads that way.

It is such a relief to get away from bursting shells that even as helpless as I am, this is like heaven.

I shall write again soon and hope to hear from you, little girl.

As ever,

Sincerely

Dick

Letter about Dick Richardson's Injury and Death

Letter about Dick Richardson's Injury and Death

Copy of a letter from Pte Frank J. Whiting of Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry (P.P.C.L.I.) to Mrs. B.P. Richardson, Grenfell, Saskatchewan

France, May 8 1917

Dear Madam,

No doubt the authorities will have notified you long ere this of the death of your son. I would have written sooner but it was not until this morning that I could get the few details I wanted. At this late date, I would hesitate to write, did I not know that there is always a certain amount of doubt about an official notification of death. Unfortunately in this case, there is not the slightest doubt as I saw the man who was with him at the end, and later buried him.

"Dick", as we called him at College and in the regiment was with his company when they made their heroic charge on Vimy Ridge on April 9th. They took the first three lines of trenches, and had got as far as the Fotie Wood on the crest of the Ridge when a German shell landed, killing two outright, and mortally wounding Dick. Two pieces passed into his abdomen, one piercing the bladder. Though badly hit, he walked part way to the dressing station, but was unable to complete the journey, and had to be carried on a stretcher. There he was laid in a partial shelter from flying fragments. He seemed in great pain for a time, though he said little, and only asked for a doctor. Unfortunately a medical officer could not be brought just then, but it would have been useless as he was dying even then. Half an hour or so later, the pain went away, and he seemed to fall asleep. This gently passed into unconsciousness, in which state he died.

As far as I can gather from questioning the stretcher bearers, he gave no final message when he knew he was dying, but if I can see anyone in the future whom he spoke to, I will send it on to you. That night he was buried in the wood and a white cross with his name and regiment marks the spot.

To me, Dick (I never learned his Christian name) was something more than my senior at College, or comrade-in-arms. He always typified everything that was straight and clean and worth while. I am a better man through having known him and many others can say the same. He was pure gold right through and possessed an intelligence that lifted him far above the petty things of life. When I welcomed back to the Company after his period in England, I chided him on coming out so soon after he was convalescent from his wound.

But apparently he thought he had not done quite his bit and could not hang around hospitals longer than he was absolutely obliged to.

In writing these few feeble lines, I have tried to convey to you the place your son held in the hearts of all who knew him. You, his mother, will appreciate him best, I know, and grieve the most, but there are many of us who claim the honour to share that feeling.

If it should be that I am spared to return to Canada, I should deem it a high privilege to meet and grasp the hand of the mother of "Dick" – Prince of men.

Believe me, I remain

Yours in deepest sympathy,

Frank J. Whiting